The changing world order, the rise of new powers and new sources of growth have been the subject of global economic and geopolitical analysis in recent years, with major implications for government economic strategy and external relations. However, it is also worth examining the basis for these – economic growth – before taking any further steps.

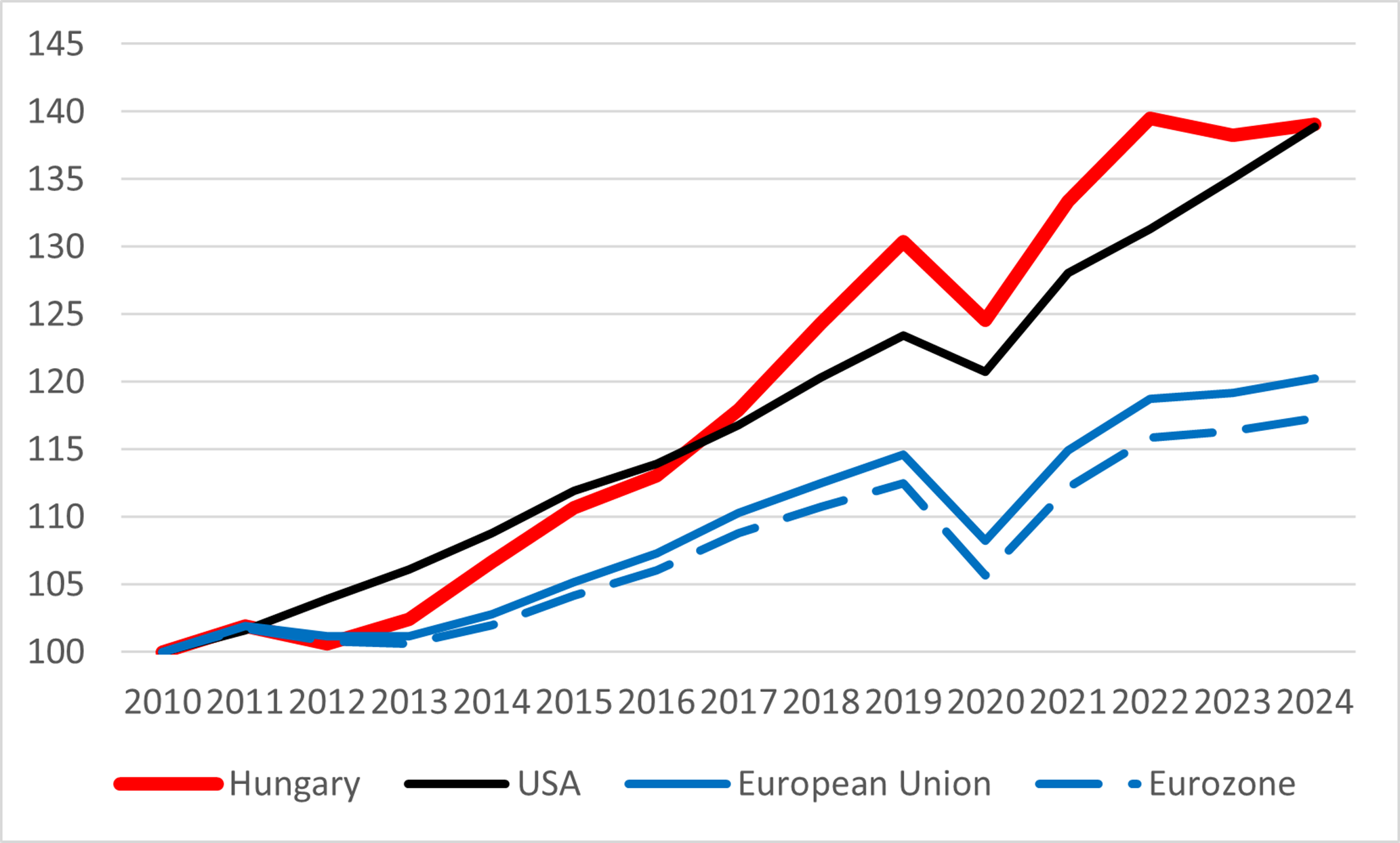

In the early 2010s, Hungary’s economic growth, in parallel with the European Union, lagged behind that of the United States. However, from the mid-2010s onwards, Hungarian growth outpaced that of the US and Europe, thanks in large part to the influx of EU aid to Hungary, but receded during the Covid-crisis to average EU levels. From 2010 to 2023, the Hungarian economy’s GDP growth (+38.2%) slightly outpaced that of the US (+35.1%), while it was significantly faster than that of the EU (+19.2%) and the euro area (+16.3%). It is important to note that large growth is easier on lower levels of development.

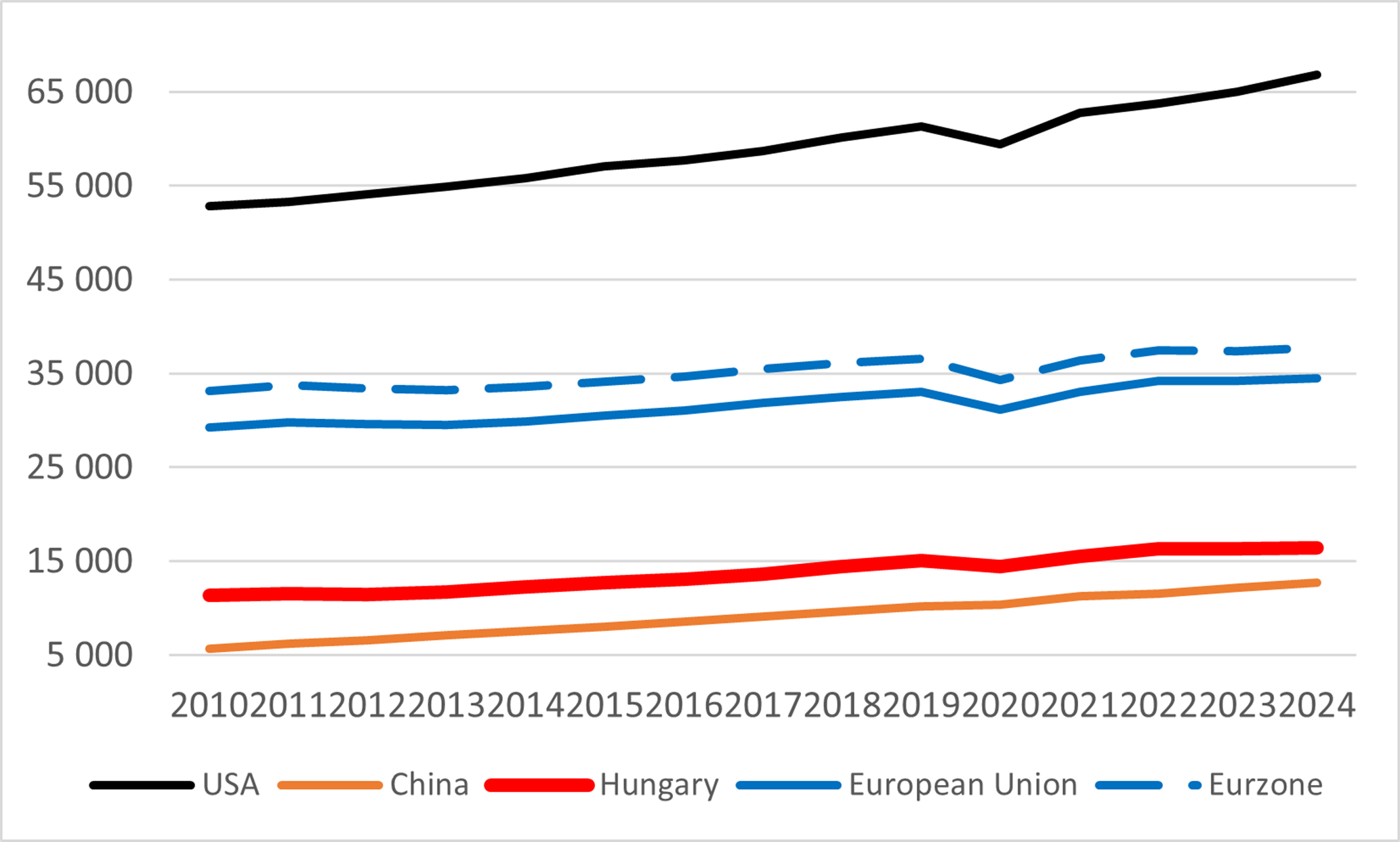

Even though the EU grew at a slower pace in percentage terms than Hungary due to a higher baseline, GDP per capita growth in dollar terms was $5,000 for both countries.

Annual real GDP growth (2010 = 100)

Source: OECD

To analyse the often foreshadowed end of the West, it is worth including the “new challenger”, China, in the analysis. Since 2010, US real GDP per capita growth has been $12,000, which is more than not only the growth in Hungary and Europe, but also the $6,500 growth in China. This means that, although Chinese GDP has grown faster than US GDP in percentage terms, in nominal terms the gap has widened, while the Hungarian ‘catch-up’ has only been sufficient to avoid falling further behind.

GDP per capita (in 2010 dollars)

Source: Worldbank

Contrary to the theories of a New World Order and ‘economic neutrality’, the Chinese economy has been converging with the Hungarian economy, not the Western one, in recent decades. At the same time, the Hungarian economy has not approached the nominal average of the European Union (despite growth in purchasing power parity), despite large amounts of EU subsidies. The growth data of recent years show that, in contrast to extensive economic development, real catch-up can only be achieved if a country engages in the production of knowledge-intensive, high value-added goods and services. In contrast to the Hungarian model, which tries to bring in simple assembly, low-wage and/or highly polluting activities with substantial direct and indirect public support. At the end of the day, the price is paid by domestic SMEs in terms of high tax burdens and weak domestic demand.