Parliament has passed the 2026 “anti-war” budget, which – according to most analysts -contains unsustainable commitments and overly optimistic macroeconomic assumptions.

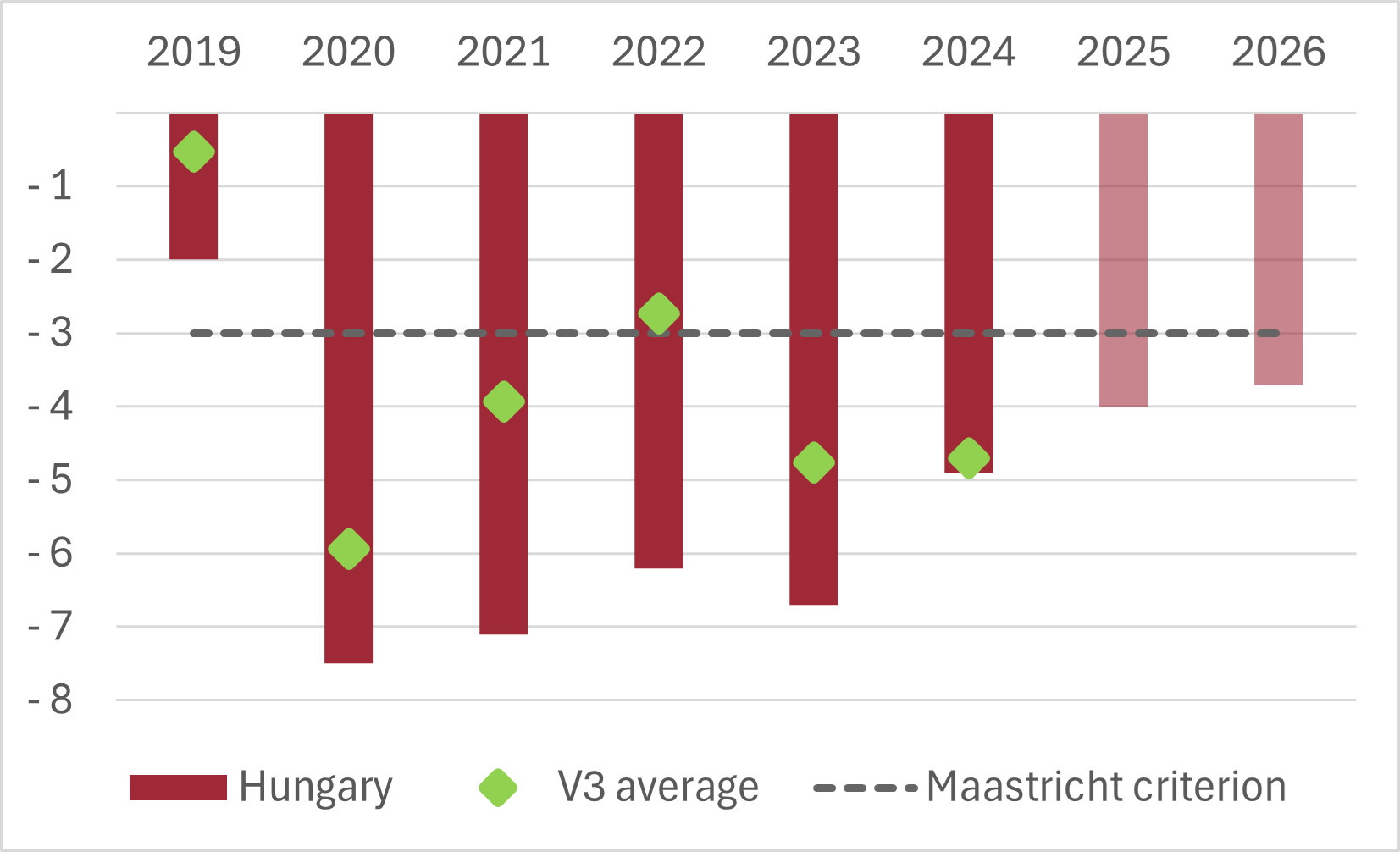

Fiscal discipline effectively ended after 2019, with Hungary’s general government deficit consistently exceeding the V3 average (Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia) year after year. This indicates that the problem is only partially attributable to external factors such as global economic trends and energy prices. Both the 2025 and 2026 budgets -despite earlier promises – project deficits above 3%, signalling that compliance with the Maastricht criteria, necessary for euro adoption, is not among the objectives of current economic policy. It is another matter entirely that even the projected deficit targets are unlikely to be met.

General Government Balance on an Accrual Basis in Hungary and the V3 (2025 and 2026: Government Projections) Source: Eurostat and the Hungarian Parliament

Source: Eurostat and the Hungarian Parliament

A significant concern is that the government’s projections for 2025 – upon which the 2026 budget is based – are themselves disconnected from economic reality. While the budget anticipates 2.5% GDP growth for this year, some experts now forecast only 0.5%, with GKI projecting 0.8% – and even that with substantial downside risks. Since actual GDP growth in 2025 will fall far short of expectations, tax revenues are also likely to underperform. This renders the planned 3.9% deficit target for 2025 obsolete; according to GKI estimates, the actual figure may approach 4.7%.

For 2026, the budget assumes 4.1% GDP growth and a 3.7% deficit. However, analyst consensus is far more pessimistic. GKI, in line with this consensus, forecasts growth of just 2.5%, implying further significant shortfalls in tax revenue. Much of the anticipated GDP growth stems from newly established factories (BMW, CATL, BYD, EVE Power), which in reality will contribute modestly to tax income due to the relatively low domestic value added.

In our assessment, labour-related payments – which are a major source of tax revenue – will constitute at most 20% of the added GDP from these facilities. Moreover, profitability during the first year of operation is uncertain. It is also unclear whether foreign workers employed in these factories will spend their earnings domestically or remit them abroad.

The budget faces contradictions on several other fronts. A projected 10.5% increase in gross average wages, combined with 3.6% inflation, implies a 6.7% rise in real wages. However, this is not supported by the anticipated 3.9% improvement in labour productivity – which would already be one of the best results in the past 15 years. It remains questionable what would drive such a sharp productivity increase, given that the average since 2010 has been only 1.1%. There is also uncertainty over how businesses would finance such robust real wage growth.

Growth prospects are further constrained by ongoing global geopolitical tensions – particularly those surrounding U.S. tariff policies and the rising energy costs linked to conflicts in the Middle East.

Domestic political dynamics are also shaping economic conditions: fiscal discipline typically weakens during election years. GKI expects a rise in government welfare spending – currently absent from the budget – in late 2025 and early 2026 as the April elections draw nearer. A potential shift in economic policy is especially relevant in the post-election period. It remains to be seen whether the political forces coming to power will commit to budgetary consolidation. Since 2010, election-year budgets have not necessarily resulted in exceptionally high deficits — but this was largely due to post-election austerity measures such as tax hikes rather than any meaningful reduction in public spending.

Despite the current environment of moderate economic growth, the government has undertaken further expenditure commitments – for instance, new tax benefits for mothers raising two, three, or more children. This has necessitated the mobilisation of new, typically higher-cost funding sources to finance the growing deficit. Concurrently, the share of foreign currency-denominated debt within the national debt portfolio has exceeded 30%, posing a risk in the event of forint depreciation. It is also worth noting that Hungary currently has the highest long-term government bond yields in the European Union (7%). This is compounded by the latest U.S. dollar bond issuance, which saw yields of 6–7% across various maturities. This financing structure significantly increases the cost of debt, placing a long-term burden on public finances.