Imagine all EU citizens shopping in a massive supermarket. Everyone tries to fill their basket equally, but not everyone can afford the same amount. According to the latest data from Eurostat, Hungarian consumers have the smallest basket of goods and services in the entire European Union.

This is not encouraging news, but is there a way out of this situation? There are indeed reasons for cautious optimism: certain areas can be improved to ensure Hungary is no longer at the bottom in terms of consumption. What are these?

- Stop the Surge in Prices

In recent years, almost everything has become more expensive (food, utilities, fuel, etc.). Prices have at times risen faster than wages. It’s as if our shopping basket keeps shrinking, even though we’re working just as hard. If prices stabilize, families can finally breathe easier, no longer forced to worry each month about what they’ll have to go without.

- Wages Should Cover Living Expenses

Many feel that “even though I got a raise, I still can’t make ends meet.” This happens because money is losing its value. The key is ensuring that wages cover more over time; not just on paper, but at the checkout counter too.

- Smarter Government Spending

The state spends vast amounts of money, but not always where it’s most needed. If more support were directed toward everyday life (childcare, healthcare, housing) families would be left with more in their pockets.

- Lower the Tax Burden

Currently, nearly every product in a Hungarian store is subject to a 27% VAT, one of the highest rates in the EU. That means one-fifth of what we spend goes straight to the state. If this rate were reduced, everyday life would become more affordable, especially for basic necessities like bread, milk, diapers, or medicine.

Why Would This Benefit Everyone?

If we have more money left over at the same prices, we can:

• Buy more;

• Provide a better quality of life for our families;

• Reduce the number of people moving abroad for work, since life at home would improve;

• Boost the economy, as higher spending fuels growth.

We don’t have to accept being last. But to move forward, government action is essential. People can only increase their consumption if they can live more comfortably on their income, if inflation doesn’t eat away at it, and taxes don’t overwhelm them.

Naturally, the reality is far more complex. The above points are merely the tip of the iceberg. In the background, deeper economic, social, and political dynamics are at play, all of which require thorough analysis. However, in order to help the public understand why Hungary currently ranks at the bottom—and what can be done about it—it is useful to start with the basics in a simplified manner. Let us now turn to what the data and analyses reveal about the underlying causes.

Each year, Eurostat publishes the AIC (Actual Individual Consumption) indicator, expressed as a percentage of the EU average for each country. This study presents the AIC trends for the year 2024 based on the latest data released by Eurostat on June 18, 2025, providing an overview of how EU member states compare.

According to Eurostat’s analysis, Hungarian household consumption was the lowest in the EU.

The AIC measures the total value of goods and services actually consumed by households, taking into account price level differences between countries. It is calculated based on per capita consumption expenditure expressed in purchasing power standards (PPS). In essence, the AIC shows how much an average resident consumes in goods and services annually relative to the EU average, adjusting for price disparities.

This makes the AIC a particularly suitable indicator for international comparisons of living standards. It is important to emphasize that AIC is a direct measure of material well-being. It includes not only goods and services directly purchased by households but also those provided by the state or non-profit organizations, such as healthcare and education, that serve household consumption.

While GDP primarily reflects economic performance, AIC more accurately captures the material welfare of the population.

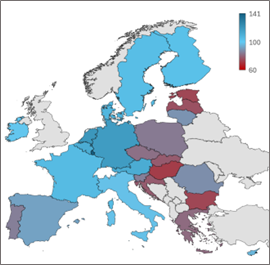

Actual Consumption Levels Across the European Union (2024)

Source: Eurostat

The highest level of Actual Individual Consumption (AIC) was recorded in Luxembourg, where consumption exceeded the EU average by 41%. Luxembourg was followed by the Netherlands and Germany, with AIC levels 20% and 18% above the average, respectively.

In addition to these frontrunners, six other member states also recorded above-average consumption—among them Belgium and Austria, both with AIC values approximately 12% higher than the EU norm.

Several major member states clustered around the EU average, within a margin of ±10%. This group included Italy and Spain, as well as Cyprus, Slovenia, Lithuania, and Portugal.

At the lower end of the EU ranking were primarily Central and Eastern European countries. In 2024, Hungary recorded the lowest AIC level in the Union, at just 72% of the EU average. Just ahead of Hungary were Bulgaria and Estonia, both at 74%. Poland and the Czech Republic approached levels between 85% and 90%.

In total, 9 EU member states reported consumption levels above the EU average, while 18 countries remained below it in 2024.

Back in 2014, the highest per capita consumption in the EU was nearly three times that of the lowest. By 2024, this ratio had narrowed to roughly twofold. This reflects a gradual convergence process, whereby consumption in poorer member states has begun to close the gap with that of wealthier countries. However, this catch-up has not been equally distributed—some countries have benefited significantly more than others.

Hungary’s Position

Between 2014 and 2023, Bulgaria consistently reported the lowest per capita consumption in the EU. While Hungary’s AIC did increase modestly: from 70% of the EU average in 2023 to 72% in 2024, Bulgaria achieved a more substantial improvement, rising from 70% to 74% in the same period.

As a result, Hungary slipped to the very bottom of the EU ranking in 2024, overtaken by Bulgaria. This marks a notable relative decline in Hungary’s position within the Union over recent years.

Hungary’s lag is particularly stark when compared to its regional peers. Earlier data had already indicated a steady erosion of Hungary’s relative standing. The long-term trend of the Hungarian AIC shows only marginal convergence toward the EU average year over year,while the region’s poorer countries have been catching up at a significantly faster pace.

In the early 2010s, countries such as Croatia, Latvia, and Estonia recorded AIC levels lower than Hungary’s relative to the EU average. Yet by 2023–2024, all three had surpassed Hungary. The same is true of Romania, which for many years trailed Hungary but has now made considerable progress and moved ahead.

In summary, Hungary has not only fallen behind the EU’s older member states, but is also losing ground relative to countries that joined the Union at the same time, or even later.

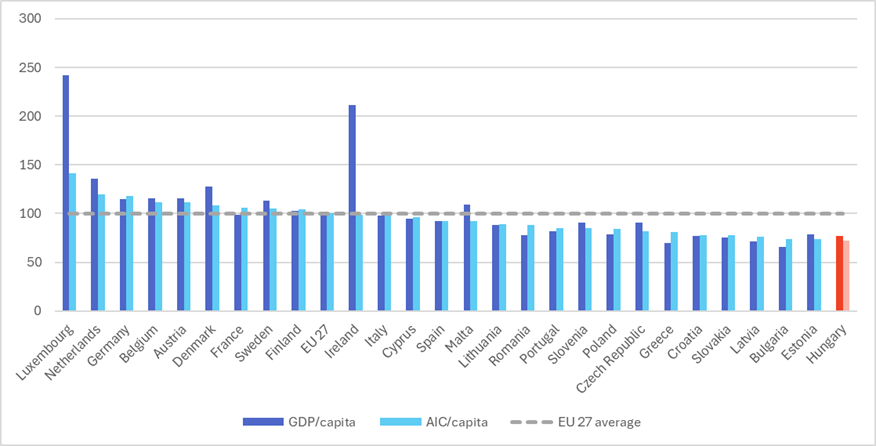

GDP per Capita and AIC per Capita in Purchasing Power Standards (PPS) Compared to the EU Average (=100%), 2024

Source: Eurostat

Relationships Between AIC, GDP, and Price Levels

The question arises as to how Actual Individual Consumption (AIC) relates to other economic indicators, particularly GDP and purchasing power. In general, GDP per capita and AIC tend to produce similar rankings, as both are tied to a country’s level of development. However, GDP figures tend to show much greater disparities, while AIC is more evenly distributed: household consumption levels vary less than GDP levels within the EU. This is because GDP includes components, such as corporate profits, capital income, and export performance, that do not necessarily appear in household consumption. By contrast, AIC more directly reflects the welfare enjoyed by households.

Hungary is a good example of how GDP and AIC rankings can diverge. In 2024, Hungary’s GDP per capita was approximately 77% of the EU average, making it only the fifth lowest among member states. However, in terms of AIC, Hungary ranked last with just 72% of the EU average. In other words, a smaller portion of the income generated in the country ends up in household consumption compared to other EU states. There are several reasons for this: firstly, a significant share of corporate profits go to foreign-owned enterprises (e.g., multinationals), and thus do not enhance domestic consumption. Secondly, the specific characteristics of income distribution and state redistribution influence how much of the GDP reaches households as consumption. Moreover, GDP can be artificially high in some countries without the population being tangibly wealthier (a classic example is Ireland, where GDP is more than twice the EU average, while AIC per capita is close to the EU average).

Purchasing power and price levels are also key to interpreting AIC, since it is expressed in Purchasing Power Standards (PPS). Therefore, the level of prices matters. In 2024, Hungary had the lowest price level in the EU for consumer goods (around 60% of the EU average). This means most goods and services are cheaper in Hungary than elsewhere in Europe. Still, even with these lower prices, Hungarians consume the least. Bulgaria has a similarly low price level (approximately 50–55% of the EU average), and its AIC is close to Hungary’s. On the other hand, countries like Denmark or Ireland have price levels 20–30% higher than the EU average, yet they also have above-average consumption. In these cases, high prices are paired with high incomes and high consumption levels. In Hungary, however, low prices are coupled with low income levels, so consumption measured in purchasing power parity also remains low.

Why Did Hungary Fall to the Bottom? Causes and Explanations

Several factors contributed to Hungary’s per capita actual consumption falling behind all other EU member states. One of the most critical was record-high inflation. In 2022 and 2023, Hungary had the highest inflation rate in the EU: in 2023, annual inflation exceeded 17%, far above the EU average. This drastically reduced real household incomes and purchasing power, as wage increases did not keep up with rising prices. As a result, the volume of household consumption fell. The high inflation was partly due to external factors (e.g., the energy price surge and the war in Ukraine), but domestic factors exacerbated the situation—such as election-related spending in 2022, loose fiscal and monetary policies, and disruptions in the food market.

Another important factor was the development of wages and incomes. While real wages in Hungary had been rising almost continuously since 2010, this growth lagged behind wage convergence in neighboring countries. In Romania and Bulgaria, for instance, wages have risen much more rapidly in the past decade (starting from a lower base), enabling higher consumption. In Hungary, by contrast, net earnings fell by the end of 2022 and into 2023.

The weakening of the forint also played a role. Although AIC is measured in PPS (so exchange rate effects appear indirectly through price levels), the persistently weak forint caused high imported inflation, further eroding purchasing power.

Long-term structural factors also explain the low level of household consumption in Hungary. The share of household consumption in GDP is relatively low compared to many other countries. One reason is that export-oriented sectors (such as the automotive and electronics industries), which make up a large portion of GDP, do not channel much of their profits into domestic consumption. A portion of the income generated flows abroad (as dividends) or is reinvested by companies rather than spent by households. Additionally, the structure of Hungary’s tax system and state redistribution plays a role: high consumption taxes (VAT, excise duties) and the erosion of the real value of certain social benefits in recent years may have suppressed household spending. Social inequality also matters: if a significant share of income is concentrated among the higher-income population, they tend to consume a smaller proportion of it, while lower-income groups, who consume most of what they earn, receive less. This too can drag down the overall AIC figure.

Demographic factors also cannot be overlooked. Hungary’s population is declining and aging. A rising share of older, inactive individuals typically moderates consumption dynamics, since pensioners have different consumption patterns and generally spend less, particularly on durable goods. While this does not directly explain Hungary’s international ranking (as other countries face similar demographic challenges), it does affect long-term consumption potential.

In summary, Hungary’s drop to the bottom of the AIC ranking is the result of a combination of factors: short-term macroeconomic shocks (especially runaway inflation), a stalled convergence process, and structural features of the economy. While other Eastern European countries have made rapid progress in terms of household consumption, Hungary’s growth has been more moderate—and has even stalled in recent years.

Consequences and Outlook

Hungary’s last-place ranking in per capita actual consumption in the EU is a serious warning sign for economic policymakers. From a policy perspective, it highlights the need to increase household disposable income and improve consumption opportunities. If domestic consumption remains persistently low, it may act as a brake on economic growth, since domestic demand is a key component of GDP. A country where people consume little is more vulnerable to fluctuations in exports and investment; a weak domestic market makes growth more uncertain, especially in times of external shocks. Therefore, policymakers should consider measures to stimulate domestic consumption—such as targeted tax cuts (especially on consumption taxes), policies to support real wage growth, and strengthening the social safety net for the most vulnerable groups.

From a social welfare standpoint, the AIC low point means that the average Hungarian household has the lowest material standard of living in the EU. In the long run, this may lead to increased emigration, as countries with higher living standards become more attractive to workers. Emigration from Hungary has already been significant in recent years; if wage and consumption convergence does not improve, this trend may continue, leading to labor shortages and demographic problems. Internal social tensions may also rise: for people’s perceived well-being and satisfaction, it is crucial that they feel their standard of living is improving. If Eurostat data clearly shows Hungary at the bottom, it can undermine public confidence and satisfaction with the government.

In terms of convergence, Hungary’s decline shows that the country has veered off the path of catching up in terms of consumption. While the goal used to be to close the gap with the EU average (both in GDP and living standards), now there is a threat of growing divergence. If this becomes a long-term trend, Hungary could find itself on the economic periphery of the EU. This would contradict the EU’s cohesion goals—after all, one purpose of EU funding and policy is to reduce living standard disparities among member states. If Hungary cannot return to a faster growth and convergence trajectory, it risks losing its relative competitiveness and appeal in the region.

Hungary’s last place in the AIC ranking is a wake-up call to improve household conditions. Boosting consumption is not only vital for individual well-being but also for the sustainable growth of the economy as a whole. This requires bringing inflation under control, supporting wage convergence, ensuring that corporate profits and productivity gains benefit household incomes, and making state redistribution more effective. If progress is made in these areas, Hungary can once again move toward convergence and gradually catch up with higher-consumption EU countries. If not, it risks falling behind permanently—posing serious economic and social challenges. These current data thus serve both as a diagnosis and a call to action: a diagnosis of where Hungary stands in terms of living standards in Europe, and a call for the necessary political and economic steps to reverse the trend.