Hungary officially has more homes than households, yet an increasing number of people feel that owning a place to live is out of reach. Social rental housing has been pushed to the margins, prices have been rising for years, and new construction remains sluggish. At the same time, more and more buyers are treating housing as a financial asset, further squeezing out first-time home seekers. How did it come to this, and what can be done?

Plenty of Housing, Yet Widespread Housing Insecurity

In 2024, Hungary had approximately 4.6 million housing units for roughly 4 million households. At first glance, the numbers suggest that housing shortages shouldn’t be an issue. But a closer look reveals a more complex picture. Some 572,000 homes remain unoccupied, 161,000 of them in Budapest alone. Many of these are either located in undesirable areas or fall short of basic standards, making them unappealing to potential residents.

Moreover, the competition is not only among those seeking a roof over their heads: investors are increasingly active in the market. Property is widely seen as a hedge against inflation or even a form of retirement savings. In recent years, 30% to 50% of new homes in Budapest have been bought not by residents, but by investors.

Compounding the problem is Hungary’s highly ownership-centric housing model. Around 90% of homes are owner-occupied, and only about 10% are rented. Within that small rental sector, social housing makes up a mere 3 percentage points, and even that share has been slowly but steadily shrinking for years. This structural imbalance fuels the broader housing crisis, manifesting in persistent homelessness, rising suburban sprawl, and the emigration of young people who see no viable path to stable housing at home.

Housing Prices Have Soared – But Why?

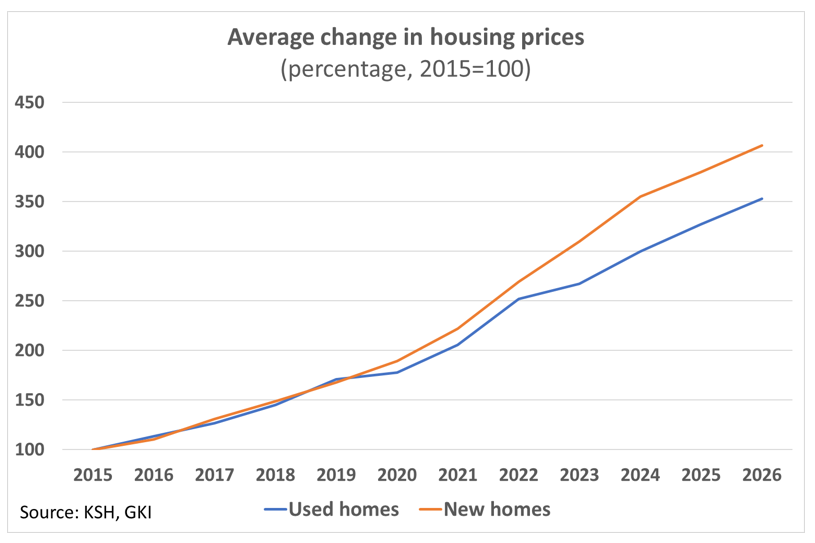

Between 2015 and 2024, housing prices in Hungary nearly tripled, pushing many out of the market, particularly young people and those on lower incomes. Demand remains high, yet the supply of new homes is strikingly limited. Hungary lags well behind its regional peers in residential construction: Poland, for example, has built four times as many new homes per capita, with the Czech Republic and Slovakia also outperforming Hungary in this regard.

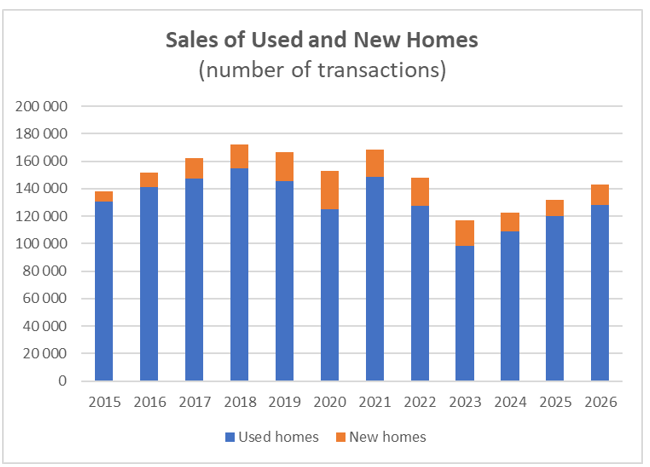

One key obstacle is regulatory instability. Frequent changes to VAT rates and unpredictable shifts in building regulations have created an uncertain environment for developers. This has had a chilling effect: in recent years, the number of new housing starts has clearly declined, reaching an eight-year low in 2024. With few new homes entering the market, demand has shifted toward existing properties, particularly in Budapest. This added pressure is driving prices even higher.

Source: KSH, GKI

State Support = Higher Prices?

In recent years, Hungary has introduced a variety of housing subsidies, from the CSOK (Family Housing Allowance) and subsidised mortgage loans, to the “Babaváró” (baby-expecting) loan scheme, reduced VAT on new homes, and the recently launched CSOK Plusz. While these programmes have aimed to support middle-class families, they have done little to assist the most vulnerable. Those with limited savings or low incomes often found themselves excluded from the benefits.

Worse, the subsidies may have driven up prices. Demand rose sharply, but supply failed to keep pace—pushing housing costs higher. At the same time, the state became the construction sector’s largest client, absorbing capacity and crowding out residential development.

Mortgage accessibility has also played a key role. In earlier years, ultra-low interest rates encouraged borrowing. When rates began to rise, many households rushed to lock in loans, further fuelling demand. In 2024, mortgage issuance more than doubled compared to the previous year.

And it’s not just private buyers: small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are increasingly entering the housing market, acquiring residential property as an investment. This additional source of demand continues to heat up an already overheated market.

Building costly in an Uncertain Environment

The construction of new housing in Hungary is becoming increasingly expensive. Rising prices for building materials, energy, and labour are pushing costs higher. At the same time, environmental regulations are tightening, imposing further burdens on developers. Unsurprisingly, these pressures are passed on to buyers, driving up property prices.

Inflation, too, is exerting a dual effect on the housing market. On the one hand, as the value of money erodes, real estate prices appear to rise steadily on paper, making property an attractive option for investors. On the other hand, household incomes are growing more slowly than housing costs, weakening purchasing power despite continued investor interest.

New policy tools, such as the HUF 200 billion state-backed equity fund dedicated to residential development, aim to support supply. But whether such interventions will be enough to offset mounting costs remains uncertain.

What Lies Ahead for the Housing Market?

Based on data from the first months of this year, trends from 2024 appear to be continuing, though the number of transactions is now showing little change. New policies such as the CSOK Plusz, along with temporary regulatory tweaks (including the use of pension savings or SZÉP card funds for housing purposes), are too limited in scope to meaningfully boost demand. However, they may still fuel price expectations and speculative sentiment.

While more building permits have been issued, these do not always translate into actual construction. Investor demand remains strong, but supply is still constrained. Price growth is unlikely to be uniform: large cities (especially Budapest, as well as Győr and Debrecen) may see further increases, while smaller towns could experience price stagnation or even mild corrections.

Without targeted intervention, housing-related challenges are likely to deepen. Addressing the issue would require a comprehensive strategy, including a well-designed support system, investment in public and affordable rental housing, and a coherent long-term housing policy. In the absence of such measures, social inequality may widen further, and for an increasing number of Hungarians, homeownership will remain out of reach.