Over the past decade, Hungary has experienced the largest increase in housing prices among European Union member states, with a cumulative rise of 237.5%, compared to the EU average of 58%. A significant portion of this surge occurred in the past two years. As a result, homeownership has become increasingly unattainable for young people and low-income households. Given the virtual non-existence of a subsidised rental housing system in Hungary, many are forced to turn to significantly more expensive market-based rental options.

The government has introduced a number of measures in previous years aimed at stimulating the real estate market (such as the Family Housing Support Programme – CSOK, the Rural CSOK, the “Baby Loan”, and the new CSOK+), which have contributed to a sharp rise in housing prices. This raises a critical question: is government intervention in market processes justified? And which factors have driven this exceptionally dynamic price growth?

GKI has analysed the key factors influencing the prices of second-hand dwellings in Budapest between 2016 and 2024. The findings indicate that the construction producer price index, 10-year government bond yields, and net wage developments are the strongest explanatory variables for housing price trends. In contrast, factors such as mortgage interest rates or the volume of housing market transactions appear to play a less significant role.

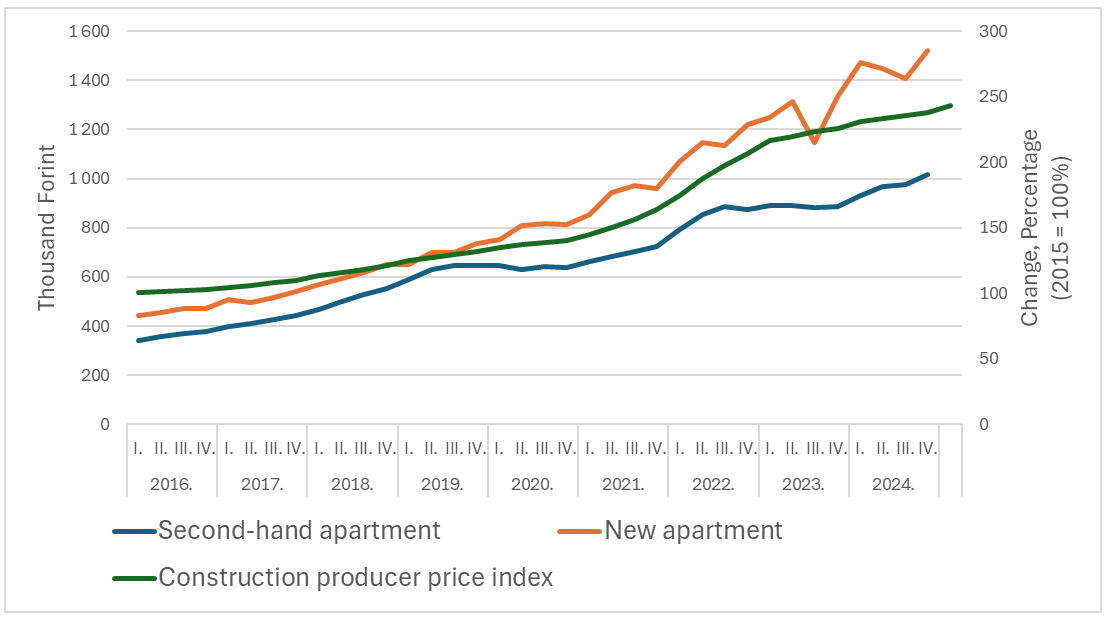

There is a near-perfect correlation (0.97) between the square metre prices of new and second-hand apartments in Budapest, indicating that the two move almost in parallel. The price increase of newly built homes—largely driven by the rise in the construction producer price index—effectively pulls up the prices of second-hand homes as well.

Average Square Metre Price of New and Second-hand Dwellings in Budapest (thousand HUF, left axis) and the Construction Producer Price Index (%, right axis)

Source: GKI calculations based on HCSO data.

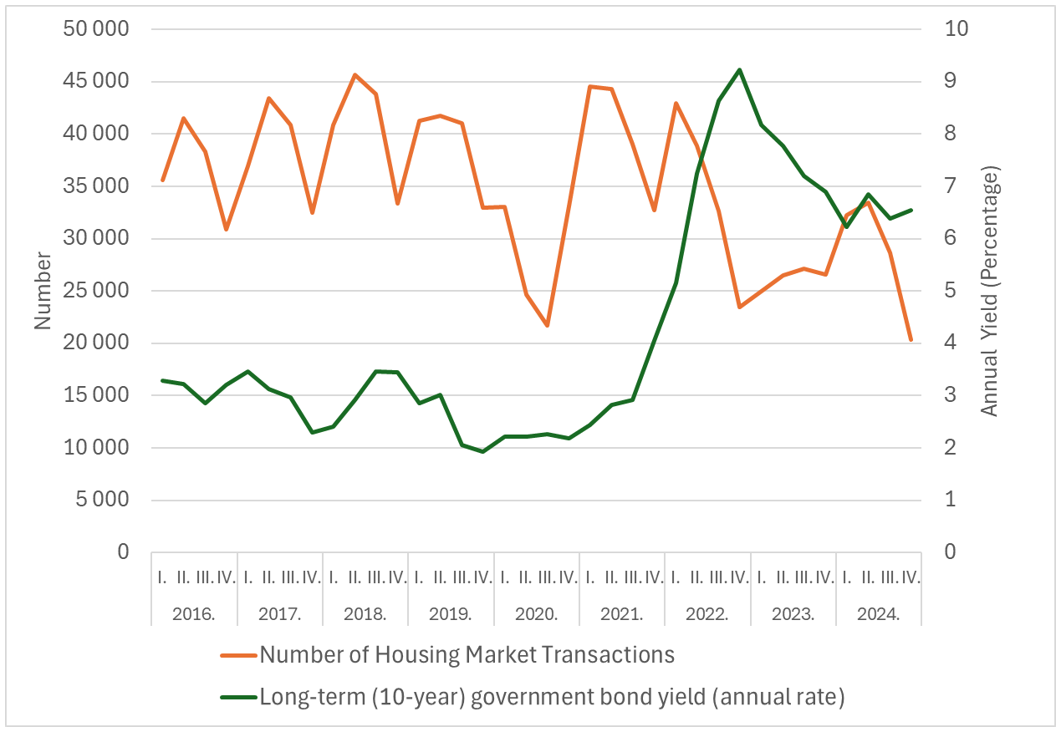

During periods of low government bond yields, investment-driven purchases accounted for a significant share of real estate market activity. Conversely, when bond yields rise or remain elevated, capital tends to shift toward government securities, leading to a noticeable decline in housing market demand. For instance, the drop in second-hand home prices observed in Q4 2022 and Q1 2023 can be attributed to a lower number of real estate transactions driven by the more attractive bond yields. In the fourth quarter of 2024, the number of housing market transactions fell to an eight-year low, signalling a substantial contraction on the demand side—effectively a market “pricing out” effect.

The rise in net wages (+170% between 2016 and 2024) has also contributed to increasing property prices. This is consistent with economic expectations: growing incomes have expanded the investable funds available to a segment of households, a significant portion of which has been channelled into the real estate market as demand.

Housing Market Transactions (number, left axis) and 10-Year Government Bond Yields (%, right axis)

Source: GKI calculations based on HCSO data.

Overall, the factors that had explained housing price developments up to 2024 pointed toward a gradual cooling of the market, which would have led to price stagnation. The construction producer price index had plateaued, government bond yields remained attractive for investors at 6.5–7%, and nominal wage growth had also slowed by 2025. As a result—combined with already extremely high square metre prices—housing market transactions declined sharply (–23%) by the end of 2024. This also dampened expectations of future price increases. When investors anticipate sustained price growth, speculative capital inflows themselves exert upward pressure on prices, reinforcing expectations in a self-fulfilling manner.

It was into this environment—ten months before the elections—that the government launched its “Home Start[1]” housing loan programme, offering mortgage loans of up to HUF 50 million at a fixed interest rate of 3%. This initiative effectively reactivates speculative motives and, under existing supply constraints, contributes to renewed price increases. According to current analyst forecasts, the loan scheme could drive housing prices up by as much as 10% within six months, and by 15–20% within a year.

The problem lies in the fact that this intervention places the programme’s intended beneficiaries—young first-time buyers with limited savings and repayment capacity—in an even more difficult position. The injection of a large volume of subsidised credit on the demand side—amid a tightening of supply—generates further price increases. Instead, a large-scale programme focused on building low-energy rental housing would genuinely help improve access to housing for those in weaker financial circumstances.

[1] A maximum HUF 50 million housing loan carries a 3% interest rate and can be used for purchasing a property with a value of up to HUF 100 million in the case of apartments and up to HUF 150 million for houses. The programme imposes no restrictions based on settlement type; it is available in both cities and villages.