The index of price increases perceived by households remains stubbornly high

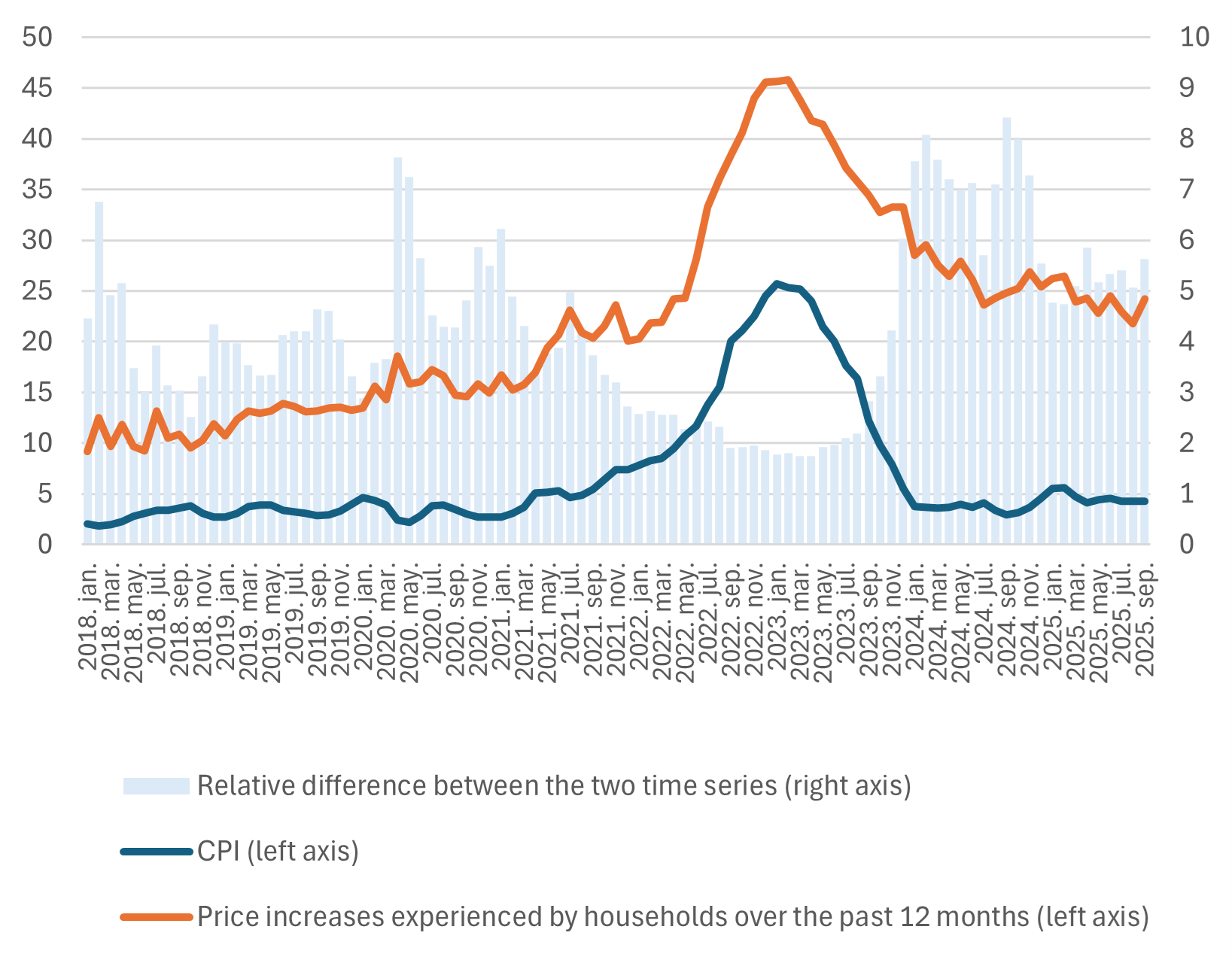

After reaching exceptionally high levels in 2022–23, the consumer price index fell below 5% by early 2024 and has since risen above that threshold only twice temporarily (the most recent figure, for September 2025, stands at 4.3%). By contrast, the indicator of perceived inflation – measuring how much households believe prices have risen over the past 12 months – has declined more slowly. As a result, the relative gap between the two measures remains elevated, even compared with levels before 2022.

Consumer price index and the rate of price increases experienced by households over the past 12 months, January 2018 – September 2025 (%)

Source: GKI survey, KSH

Note: The relative difference shows how many times the values of the two time series diverge from each other.

Households’ perception of inflation often diverges sharply from official figures. One reason is that individual households have different patterns of spending on goods and services, meaning the official consumer price index does not necessarily reflect each household’s costs. People also tend to gauge inflation based on their own experiences. If the price of a frequently purchased item rises rapidly while others remain stable, households perceive a higher inflation rate than the economy-wide average. This effect is especially pronounced during crises or periods of uncertainty, when fears about inflation intensify. Even if actual price increases are modest, anxiety or pessimism can amplify the sense of inflation. Moreover, repeated exposure to news about rising prices tends to heighten households’ perception of inflation.

It is also evident that among different social groups, the smallest gap between perceived and official inflation is observed among university graduates and those in the top income decile. Conversely, the largest discrepancies are found among those with only primary education, the lowest income decile, and people over 65. During Hungary’s period of high inflation, prices of essential goods and services rose faster than those of durable, infrequently purchased items – affecting low-income households more acutely, a group whose share has grown precisely because of high inflation. The lower a household’s income, the larger the proportion spent on basic necessities – food, utilities, housing – which tend to be price inelastic (purchased even as prices rise). Many under-30s still live with their parents and typically do not handle their own shopping, so their inflation expectations differ from those of their parents. On the other hand, older people rarely buy high-value items, such as household appliances or cars, meaning price changes in these goods have little direct impact on them.

The gap between households’ perception of price changes and the official figures published by the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH) fluctuated sharply between 2018 and 2025. Up to 2021, on average, households perceived inflation to be four to five times higher than the consumer price index. During much of 2022 and 2023, however, this multiple fell below two, indicating that households were less prone to overestimating official inflation. By 2024, the perceived inflation gap surged to more than seven times the official rate, before falling back to roughly five times by the end of the year – a level it has since maintained. As a result, although the KSH data show that the consumer price index’s rise has slowed markedly, remaining persistently below 5%, households do not feel this deceleration.