The forint has strengthened steadily against the euro in recent months; over the past eleven months the Hungarian currency has appreciated by 7.3%. The last time the forint was this strong against the euro was in January 2024. This development has economy-wide implications: it fundamentally influences export performance, household consumption, the inflation trajectory and, ultimately, gross domestic product (GDP). In this analysis, we examine the short- and long-term growth effects of the forint’s appreciation on the basis of our model calculations.

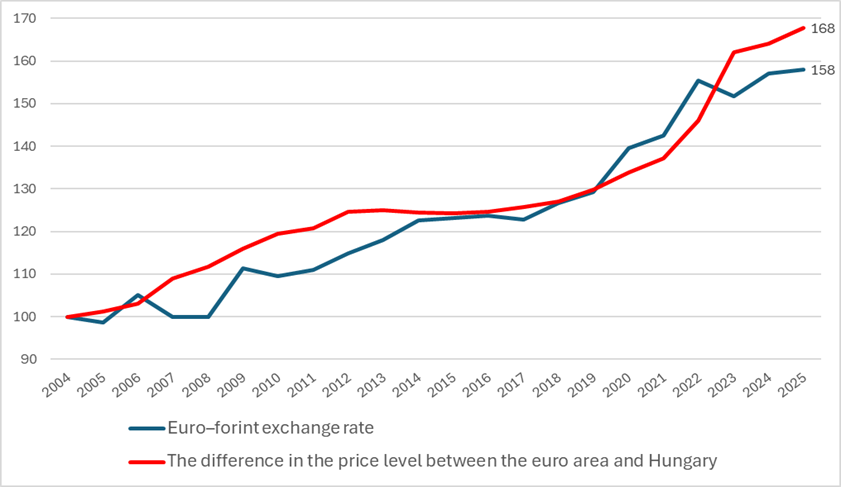

From Hungary’s accession to the European Union in 2004 until 2024, the euro–forint exchange rate was driven primarily by the inflation differential between the euro area and Hungary. In practice, this meant that the domestic currency depreciated roughly in line with the extent to which Hungarian price increases outpaced those in the euro area. Since 2004, prices have risen 68% more in Hungary than in the eurozone, while the forint has depreciated by 58% against the euro. From 2023 onwards, however, the two indicators began to diverge: Hungary’s higher inflation relative to the euro area has been reflected less and less in exchange-rate movements—in other words, the forint has appreciated in real terms. In 2025 the inflation gap between the euro area and Hungary stood at 2.3 percentage points, while the euro’s annual average exchange rate rose only from 395.3 to 397.8, an increase of merely 0.6%. The divergence between the two indicators thus reached 10 percentage points in 2025.

Developments in the euro–forint exchange rate and the price-level differential between the euro area and Hungary (2004=100%)

Source: Eurostat, GKI calculations

The appreciation of the exchange rate sets in motion opposing economic processes over time, with distinct short- and long-term effects. In its initial phase, the short-term impact is favourable for households, as a stronger currency primarily reduces import prices and thereby moderates the consumer price index (inflation). Lower consumer prices raise real incomes, which in turn stimulates household consumption.

Running parallel to this, however, is a more slowly unfolding effect in the opposite direction through exports. While domestically measured costs—denominated in forints—rise, the strengthening currency means that export revenues converted into forints decline for a given export volume. In other words, an appreciating domestic currency can erode competitiveness in international markets. This particularly affects domestically owned exporting firms with a high share of local inputs and wage costs—namely export-oriented sectors with high domestic value added. By contrast, large multinational companies that rely heavily on imported inputs, and whose costs are only partly incurred in forints, experience this effect to a lesser degree.

Hungarian firms producing for the domestic market must contend not only with rising wage and other costs, but also with intensifying price competition from cheaper imports in their own markets. The tourism sector is likewise affected. Hungary becomes more expensive for foreign visitors, potentially weakening the country’s appeal as a destination, while foreign travel becomes cheaper for Hungarian residents. Unless this loss of competitiveness is offset by a meaningful improvement in productivity, a stronger forint may exert a dampening effect on GDP growth in the long run, in contrast to the rapid but temporary benefits of lower inflation.

Our modelling results suggest that in the first quarter following a one percentage point appreciation of the forint, the resulting moderation in consumer prices contributes approximately +0.4 percentage points to economic growth, and +0.1 percentage points in the second quarter, owing to stronger consumption. A stronger currency could also support growth if it were accompanied by lower interest rates, as declining borrowing costs would stimulate investment. At present, however, the forint’s strength is itself a consequence of high interest rates, meaning this channel is not operative.

From the third quarter onward (–0.2 percentage points), the sign of the effect reverses, and the appreciation begins to slow the pace of economic growth. Thereafter, the restraining effect intensifies (around –0.3 to –0.4 percentage points per quarter). The reason is that previously accumulated import inventories purchased at higher prices are gradually run down, and increasingly cheaper imports enter the market. As price competition strengthens, the profitability of domestic firms declines, leading to weaker performance—even though their own import costs also fall. This, together with the changing position of export-oriented producers, reduces exports and affects the external balance through a decline in net exports, which in turn exerts a further negative impact on GDP.