Hungary is regarded by credit-rating agencies as one of the European Union’s most risky countries. Hungary’s public debt currently sits at the lower end of the investment-grade category. At one of the three major rating agencies (S&P), only a single notch separates the country from “junk” (not recommended for investment) status. We have previously examined the criteria used by credit-rating agencies; in this article, we look at the potential consequences of a downgrade and at Hungary’s domestic outlook.

What does a downgrade mean?

A downgrade typically leads to a rise in risk premia: investors are willing to finance the sovereign only at higher yields, especially in the short term, when portfolios are being repriced. Some institutional investors are constrained by their mandates from holding assets that fall into the non-investment-grade category, triggering forced reductions in holdings and temporary liquidity pressure. The direct consequence is an increase in the average cost of financing public debt and a rise in interest expenditure, creating a need for fiscal consolidation within the budget.

Risks also emerge on the exchange-rate side: a deterioration in perceptions can generate currency pressure, which feeds through import prices into higher inflation. This is unfavourable for monetary policy: concerns over the sustainability of disinflation and financial-stability risks narrow the scope for any easing. A worsening yield environment also raises the cost of financing for firms and households, feeding back into domestic demand and investment.

What are the prospects?

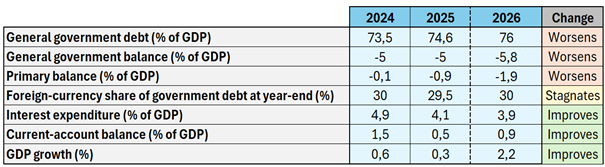

It is difficult to discern what goes on in the credit-rating agencies’ “black box”, but several factors are explicitly given significant weight in the assessment of sovereign risk.A key factor is the evolution of the deficit and public debt. According to GKI, in 2026 – primarily due to income outflows and revenue shortfalls related to the elections – both indicators are set to rise significantly. Although government investment has been restrained, measures such as the six-month military bonus, the personal-income-tax relief for mothers with two or three children, the doubling of the family tax credit, and the one-week payment of the 14th-month pension all weigh on the budget, as does GDP growth falling short of projections. While interest expenditure declines thanks to an improving global rate environment, the primary balance – that is, the fiscal balance excluding interest payments – deteriorates.

Trends in selected indicators monitored by major credit-rating agencies

Source: 2024: MNB, ÁKK, KT. 2025-2026: GKI estimation and forecast

The share of public debt denominated in foreign currency is particularly important, as indebtedness in foreign currencies carries significantly higher risk. In such cases, the central bank’s room for manoeuvre is limited: it cannot indirectly finance public debt by issuing its own currency – so-called “money printing.” Moreover, the budget primarily collects revenues in forints, meaning that any depreciation of the domestic currency would also raise interest costs on foreign-currency bonds.

By the end of 2024, the share of public debt denominated in foreign currency approached 30% and briefly exceeded it. By the end of 2025, the indicator again settled between 29% and 30%. The Government Debt Management Agency has repeatedly emphasised the importance of the 30% threshold, while GKI does not forecast any significant change in this respect in 2026.

The risk of a downgrade is mitigated by the economy finally accelerating this year: GDP growth of 2.2% is expected in 2026. At the same time, Hungary’s current-account balance is projected to improve further, contingent on a revival in export markets. Beyond fiscal indicators, credit-rating agencies also consider the stability of institutional structures and the predictability of economic-policy decision-making.

How can the risk of a downgrade be mitigated?

If a credit-rating agency expects risks to persist or sees a weakening of the sovereign’s credit profile, its decision on the rating or outlook will tend to tighten. According to the logic of the agencies, the issue is not a single event, but rather the overall trajectory of fiscal policy, growth prospects, inflation and exchange-rate exposures, external financing, and institutional predictability. If these factors evolve favourably from the agencies’ perspective, a downgrade can be avoided.

There are three main arguments for maintaining the current rating. First, according to GKI forecasts, economic growth is set to accelerate to 2.2% in 2026, the current-account balance is improving, and export markets are picking up. Second, the share of public debt denominated in foreign currency has stabilised around 29–30%, remaining below the critical 30% threshold. Third, the declining international interest-rate environment eases the burden of interest payments.

At the same time, GKI identifies three significant risks. According to its forecasts, the budget deficit and public-debt ratio are expected to rise sharply in 2026, primarily because of income outflows and revenue shortfalls related to the elections. The primary balance deteriorates, while the lasting impact of election spending – such as the military bonus, tax reliefs, and the 14th-month pension – weighs on the budget. Frequent fiscal adjustments and the unpredictability of economic policy further undermine investor confidence.

Under the most likely scenario, the rating agencies will hold off during the first half of 2026 but signal a warning: if a credible consolidation programme is not launched after the elections and the primary balance does not improve, a downgrade is expected. The critical period will be the third quarter of 2026 and the first half of 2027, when it becomes clear whether the current government is genuinely committed to fiscal consolidation. If it is not, the agencies will take the first step toward a downgrade.